Kaitlyn MacInnis is a former student in the Department of History at SFU. She normally focuses on Britain, but working as a Research Assistant for Dr. McCullough has afforded her the opportunity to learn more about settler colonialism on the Indigenous lands where she was raised. With broader public discussions of renaming focused on powerful and overtly heinous colonisers, she wanted to explore a more mundane example of settler commemoration through naming. Update: Kaitlyn will begin her PhD in the Department of History at SFU in the Fall of 2021.

—

With lifted arms let’s seize our toil-right,

We’ll take it, wear it, ‘tis our own.

[. . .]

Then when retired and freed from labor,

Triumphantly we’ll tread the plain,

Then Fortune’s pencil shall be waiting

To write our names in book of fame.

–From “The Path Before Us,” in the newspaper published on the ship carrying the Columbia Detachment of the Royal Engineers from Britain[1]

…

John Linn was likely born in 1815 in the small parish of Corstorphine, just west of Edinburgh. His training in stonemasonry allowed him in 1846 to pursue broader horizons through enlistment with the Royal Sappers and Miners, an elite corps of the British Army often deployed in civil as well as military building work, which was absorbed in 1856 into the officer corps of the Royal Engineers. It was while stationed in Halifax as a Sapper that Linn met his wife Mary Robertson, originally from Broadford on the Isle of Skye.[2]

[Image 1] “Mr. and Mrs. John Linn,” c. 1865.

[Image 2] Group assembled outside tents at Linn’s Cottage at Lynn Creek [1896?]. After the Linn family left, the land was used recreationally by settlers.

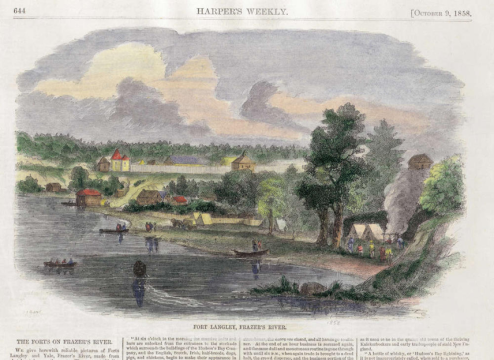

[Image 3] Commemorations such as New Westminster’s “The Sappers Were Here” sign perpetuate the settler-colonial narrative. Photo by John Sinal.

[Image 4] The Fisherman, Sept. 12, 1958.

One early settler historian who wrote about the Linns was anxious that the memory of local pioneers “should not suffer the fate of eternal oblivion.”[12] This concern demonstrates the importance of pioneer mythology in ongoing colonisation, but also hints at the lack of “rootedness” of settlers and settler names, by contrast with the deep histories of Indigenous peoples on the land, and the meaningful names they impart to it.[13] Lynn Creek is a case in point. The first settler name, although in use during the Linns’ tenancy, didn’t last: “Fred Creek,” after Fred Howson, who had pre-empted the land in 1863 and abandoned it shortly thereafter.[14] The Linns may have made more of a mark on local settler memory, but Fred Howson didn’t set a high bar to clear. All told, the Linn family occupied the land for about twenty-one years, and the land was sold for a large sum almost as soon as it became legally possible to do so.[15] When one of the last surviving Linn children was interviewed in 1953, she declared “that she wouldn’t care to go back in the valley to live,” there being “nothing much there to attract her any more.”[16]

[Image 5] “Lynn Creek,” by James Crookall, between 1918 and 1928.

© Kaitlyn MacInnis, 2020

The author is grateful to Dr. Rudy Reimer for providing clarification regarding First Nations territories, and to the staff at North Vancouver Museum and Archives for facilitating research.

Images

[Image 1] “Mr. and Mrs. John Linn,” c. 1865, City of Vancouver Archives, AM54-S4-2-: CVA 371-1257.

[Image 2] Group assembled outside tents at Linn’s Cottage at Lynn Creek [1896?], City of Vancouver Archives, AM54-S4-: SGN 356.

[Image 3] “The Sappers Were Here” by John Sinal. Copyright 2018 Wesgroup Properties and The Brewery District Investment Ltd.

[Image 4] The Fisherman, Sept. 12, 1958, SFU Digitized Newspapers.

[Image 5] “Lynn Creek,” by James Crookall, between 1918 and 1928. City of Vancouver Archives, AM640-S1-F2-: CVA 260-1194.159.

Notes

[1] The Emigrant Soldiers’ Gazette, and Cape Horn Chronicle, 11 December 1858, 4, UBC Library Open Collections, https://open.library.ubc.ca/collections/bcbooks/items/1.0222082 – p33z-3r0f:.

[2] On John Linn and the Linn family, see especially: Judy Koren, Family Histories Item 1158, North Vancouver Museum and Archives; Walter Draycott, Early Days in Lynn Valley (North Vancouver: The North Shore Times, 1978), 7-9; James Skitt Matthews, Early Vancouver (Vancouver: City of Vancouver, 2011), vols 3 (91) and 4 (138-140), http://former.vancouver.ca/ctyclerk/archives/digitized/EarlyVan/index.htm.

[3] https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/fraser-river-gold-rush

[4] John Linn to Frederick Seymour, 18 July 1865, GR-1372.89.1001, Royal BC Museum and Archives, https://search-bcarchives.royalbcmuseum.bc.ca/linn-john.

[5] Elizabeth Furniss, “Pioneers, Progress, and the Myth of the Frontier: The Landscape of Public History in Rural British Columbia,” BC Studies no. 115/116 (Autumn/Winter 1997/98): 13.

[6] On the Royal Engineers’ instrumental role in colonisation, through an uncritical settler lens, see Beth Hill, Sappers: The Royal Engineers in British Columbia (Ganges, BC: Horsdal and Schubart, 1987); Frances M. Woodward, “The Influence of the Royal Engineers in the Development of British Columbia,” BC Studies no. 24 (Winter 1974-75): 3-51.

[7] On the colonising role of settler families, including the children of the Royal Engineers—long celebrated in pioneer mythology—see Laura Ishiguro, “‘Growing up and grown up . . . in our future city’: Children and the Aspirational Politics of Settler Futurity and Colonial British Columbia,” BC Studies no. 190 (Summer 2016): 15-37.

[8] See the language in the epigraph. Through its self-mythologisation and its representations of First Nations peoples, The Emigrant Soldiers’ Gazette was in some regards an explicit primer for colonisation.

[9] Mac Reynolds, “When Linns Lived Beside Lynn Creek,” Vancouver Sun, 28 March 1953, 18; Furniss, “Myth of the Frontier,” 22-23.

[10] Amanda Murphyao and Kelly Black, “Unsettling Settler Belonging: (Re)naming and Territory Making in the Pacific Northwest,” American Review of Canadian Studies 45, no. 3 (2015): 316.

[11] Cairns Craig, The Wealth of the Nation: Scotland, Culture and Independence (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2018), 63-72.

[12] W.M.L Draycott, “Foreword,” in Lynn Valley: From the Wilds of Nature to Civilization [. . .] (North Vancouver: North Shore Press, [1919]). http://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.9_91613/2?r=0&s=1

[13] Murphyao and Black, “Unsettling Settler Belonging,” 322-323; Christina Gray and Daniel Rück, “Reclaiming Indigenous Place Names,” Yellowhead Institute, https://yellowheadinstitute.org/2019/10/08/reclaiming-indigenous-place-names/.

[14] First Nations and Asian people were excluded by law from the right of pre-emption. Timothy J. Stanley, “Commemorating John A. Macdonald: Collective Remembering and the Structure of Settler Colonialism in British Columbia,” BC Studies no. 204 (2020): 110.

[15] Because John died without a will, “his” property could not be disposed of until his youngest child turned twenty-one.

[16] Reynolds, “When Linns Lived Beside Lynn Creek,” Vancouver Sun, 28 March 1953, 18.

[17] Gikino’amaagewinini, “Naming as Theft and Misdirection,” BC Studies no. 195 (Autumn 2017): 107.

[18] Draycott, Early Days, 7.

[19] Tansi Nîtôtemtik, “What’s in a Name? Renaming and Reclaiming of Indigenous Space,” University of Alberta Faculty of Law Blog, 9 November 2018, https://ualbertalaw.typepad.com/faculty/2018/11/whats-in-a-name-renaming-and-reclaiming-of-indigenous-space-.html.